Sunstein Insights

Pay for Delay” Settlements: The FTC ‘s 2010 Annual Report

The Hatch-Waxman Act requires that patent litigation settlement agreements between pioneer and generic drug makers be submitted to the Federal Trade Commission, which must release an annual report summarizing them.

This year’s report was recently published, and it reflects the FTC’s continuing disdain for so-called ”pay for delay” settlements of patent litigation in which a pioneer drug manufacturer pays a generic drug maker to stay out of the market for some or all of the remaining term of the patent. The FTC believes that such payments are no more than an illegal payoff to prevent generic drug competition. To the FTC’s great dismay, few courts agree with its position.

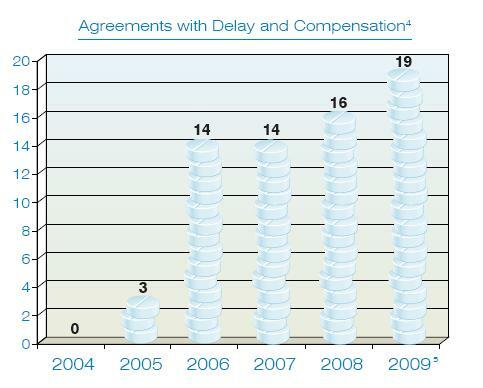

This year’s report contains a simple chart, reprinted below, that documents the extent to which the tide has turned since 2004, when the FTC had convinced the entire industry that such settlement agreements would result in nothing but trouble:

In 2005, the 11th Circuit handed the FTC its first defeat on this issue, ruling that settlements in which the generic drug company receives compensation (which we have called “reverse payment” agreements in prior articles) are not a per se violation of the antitrust laws. As the table shows, the effect was immediate and dramatic: The number of such settlements has grown as additional courts of appeals, including the Second and Federal Circuits, have found reason to uphold the legality of such settlements.

This year’s report is more detailed and emphatic than in previous years. It reports that about 24% of all settlements between pioneer and generic drug makers involve reverse payments. The report argues that, on average, reverse payment settlements prohibit generic entry for nearly 17 months, costing consumers $3.5 billion annually. The FTC also repeats its prior calls to Congress to include an outright ban on reverse payment settlements in the pending health insurance legislation.

To date, the bills that would outlaw reverse payments have not made their way into the health insurance legislation. Instead, they are locked up in committee, where they tend to die each year at the behest of lobbyists for the pharmaceutical industry.

The FTC also repeats its finding from a 10-year study first published in 2002 which concluded that generic drug companies prevail in 73% of their patent lawsuits with pioneer drug companies.

The FTC’s calculus is clear: Since generic drug companies usually win when forced to carry on with their litigation, the best way to thwart suspect patent filings by pioneer drug companies is to forbid settlement of patent litigation. In other words, cage fighting between generic and pioneer drug companies is good for consumers.

In making its argument, the FTC is sometimes guilty of overstating its case. For example, the report states: “Settlements with first filer generics can prevent allgeneric entry. Those agreements place a ‘cork in the bottle’ that typically ensures the brand name drug’s lock on the market.”

It was once true that a settlement agreement between a pioneer drug maker and the first generic company to challenge its patents could be structured to prevent the FDA from approving any other generic application for the same drug. This statutory problem was solved in 2003 when forfeiture provisions were added to the Hatch-Waxman Act.

Under the revised law, the first generic challenger has a brief period of time to market its product after the settlement of the patent litigation. If it fails to do so, then the FDA may approve other generic application and the first challenger will lose its statutory right to a 180-day period of exclusivity.

While this statutory solution was mentioned indirectly in a footnote in the FTC report, the description of this solution is provided in sketchy terms that do not do justice to the legislation. Of course the pioneer drug company may assert its patents against those drug makers, so generic entry is not guaranteed, but that is to be expected when a patent protects the drug. In short, the FTC’s claim that there is a ‘cork in the bottle’ when reverse payment settlement agreements are reached is simply not correct.

The FTC’s 2010 Annual Report is a testament to its inability to persuade others, including the Courts of Appeals and the Justice Department, that reverse payments are a clear-cut antitrust violation. It puts a price tag on these settlements: $3.5 billion annually. And it beseeches Congress for statutory help.

Given the recent election results in Massachusetts, it seems likely that any health insurance bill that may be passed this year will have teeth removed, not added. Thus, the FTC will issue a very similar report next year, again seeking allies in its lonely fight against reverse payments.

Most Popular

-

Massachusetts Jury Sets New Record Under Federal Defend Trade Secrets Act With $452 Million Damages Award

-

New Trademark Office Fees Increase Cost, Headaches

-

The New York Times v. OpenAI: The Biggest IP Case Ever

-

Advertisers Beware: Falsely Advertising Products as “Patented” and “Proprietary” Can Violate the Lanham Act, Says the Federal Circuit

-

Corporate Transparency Act: To File or Not to File?

-

Wavy Baby Waves Goodbye to its Attempt at Humor

We use cookies to improve your site experience, distinguish you from other users and support the marketing of our services. These cookies may store your personal information. By continuing to use our website, you agree to the storing of cookies on your device. For more information, please visit our Privacy Notice.